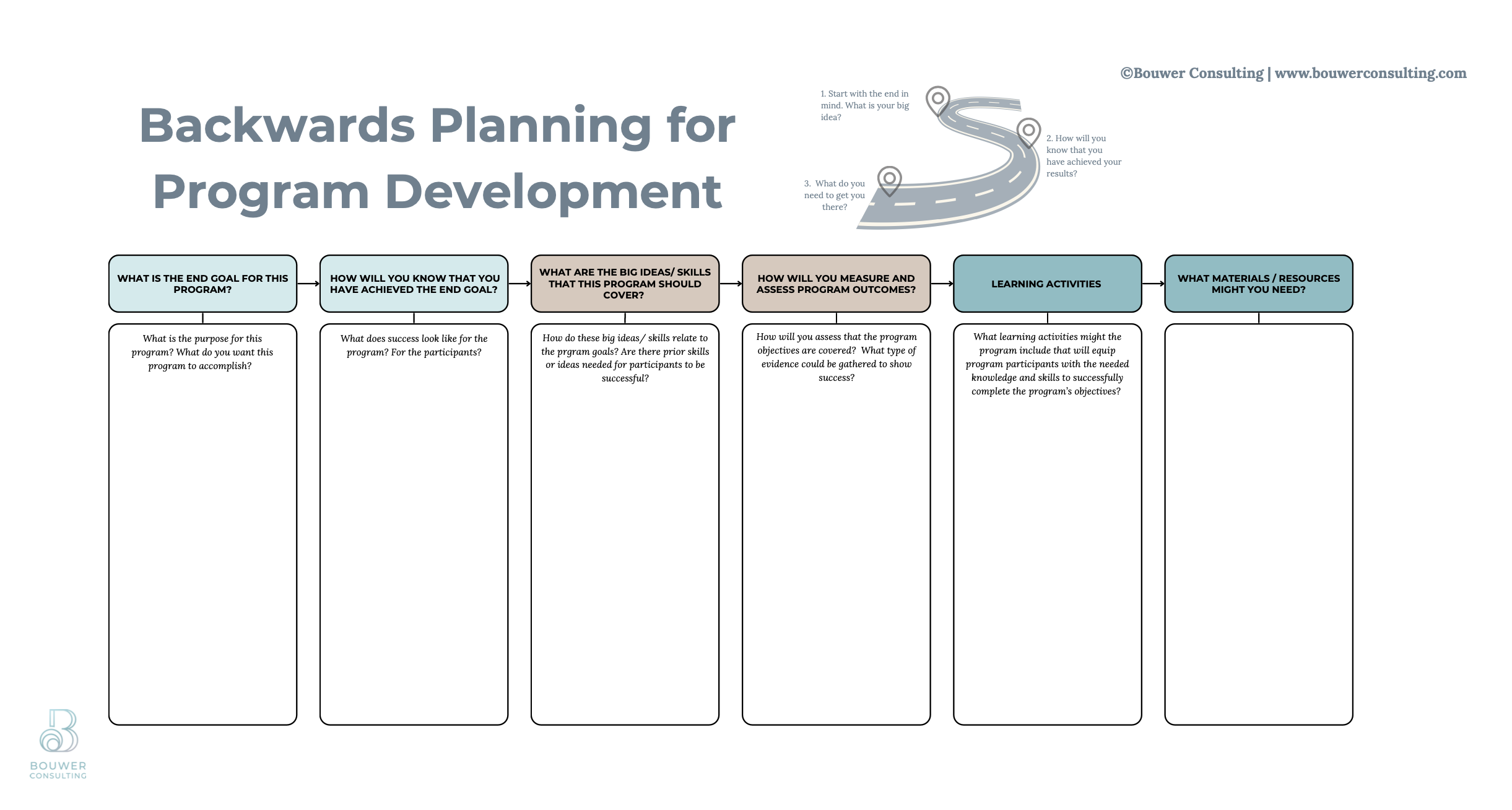

#8: The Importance of Backwards Planning

“Backwards planning ensures that each step taken is purposeful and contributes meaningfully to the overall success of the program.”

Click below for our free PDF “Backwards Planning” Template

Not long ago I was introduced to the Karez water systems, a phenomenal engineering feat that is still used in Western China today.

Located in Turpan, a beautiful region surrounded by desert and the nearby Flaming Mountains, this amazing irrigation system was built to solve the problem of a steady water supply.

In an area that had very little water, and yet grows some of the sweetest grapes I’ve ever had, I was amazed at how this 1,000 year old irrigation system was built using backwards planning.

Karez irrigation- Turpan, China

Looking around at the dry, dusty region, it is clear that water is a precious resource. Instead of focusing on the problem, limited water, what I found inspiring was how these ancient people groups re-framed their perspective. Looking to the distant mountain chain that had snow, the question became: how can melting snow be used for a regular water supply without it evaporating or having sand blown into it?

The answer: use the gravity of the downward slope of the Turpan Depression to create an intricate underground collection of canals, to connect a network of wells.

By using the natural land formation, they were able to guide the water directly to the plants with minimum water evaporation. What was even more mind blowing is that this underground network- built by hand!- spanned well over 5,000 km in length!

Cultivating A Backwards Approach

As I was visiting the working Karez system, I was thinking about how the backward planning approach applies to program development. Often individuals have an idea or see a problem that they feel needs to be fixed. After gathering a few ideas, they begin to move forward, figuring it out as they go along. There’s often a thought that they just need to move forward and as movement occurs, things will be sorted out and the new program will solve the issue that they are facing. Phrases such as, ‘opportunity to practice flexibility’ and ‘we just need to adjust and adapt’ are often spoken in team meetings when hurdles are met. While these are valid practices, I am often left wondering if programs might look different had the starting point been the end goal.

Oil lamp orientation- while digging these tunnels by hands, oil lamps not only lit the tunnel, but if the flame shook, it meant a landslide was occurring in the culvert and the karez worker could escape in time. More importantly, lamps were placed every 2-3 meters along the the culvert. If the digger could see only 1 lamp behind him, he knew he was digging straight. If he could see 2 or 3 lamps it meant he was no longer digging straight and needed to adjust. Amazing!

Starting With The End In Mind

In the process of building the Karez system, the start was actually the end goal in mind. They didn’t start digging wells randomly with hopes of finding water and arbitrarily plant their vineyards near that source. Rather they focused on the end result first:

What was their goal? A steady water supply for agricultural use;

What was the tangible outcome of the goal they hoped to accomplish? An oasis that could support the growth of fruits and livestock.

From there they worked backwards to determine the steps and plans needed for a sustainable outcome, one that has lived on and continues to be used today.

Some of the sweetest grapes come from this valley!

Returning to program development, the best programs that are designed and built, start with the end in mind- not just the final desired outcome, but the tangible results that you are able to see for the desired outcome.

To do this, one must not only have the broader goal objective, but also the specific indicators that tell you if your desired goal has been met.

From Vision to Reality

For example, one program that I was asked to help revise and develop had a broad objective: providing student choice courses that provided “real life skills” and “meaningful processes”.

So what was the process to turn this goal into tangible outcomes to determine if the program being offered was meeting the broad objective?

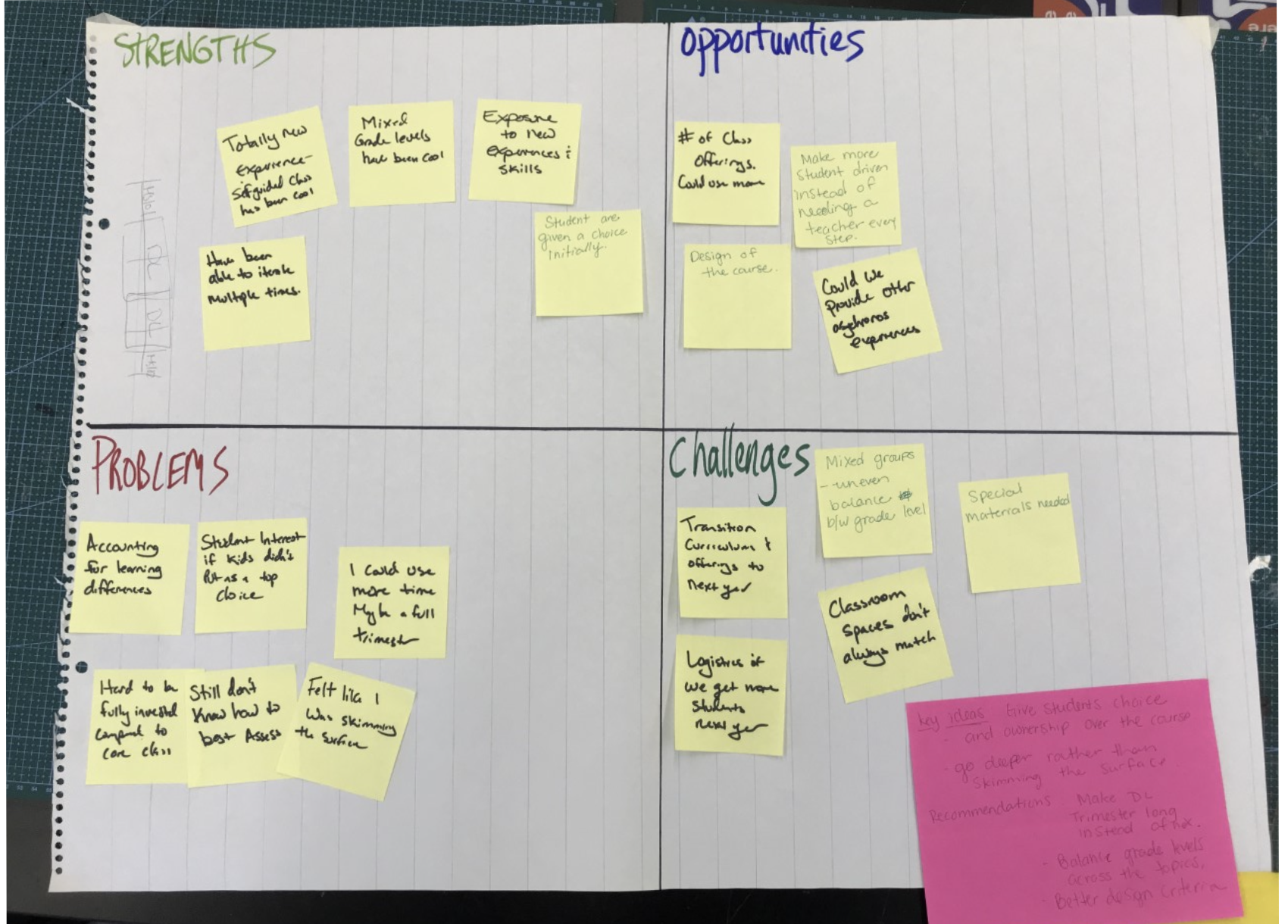

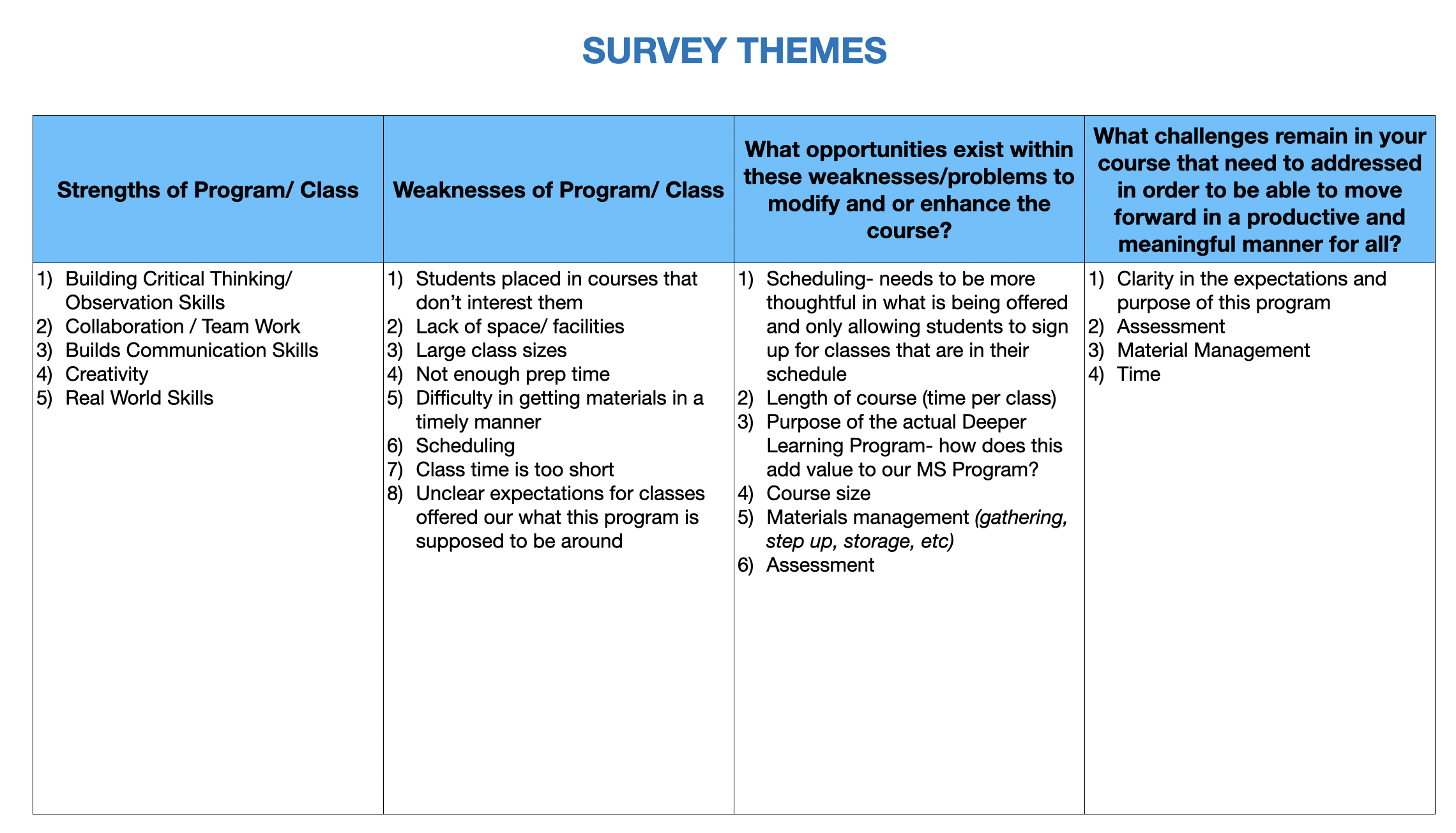

To start, we looked at all the data and did a check-in SWAT analysis with focus groups consisting of those who were currently implementing courses inside this program. Hearing different perspectives was incredibly important because these stakeholders were the ones that were actually implementing the program, so their voice and input was key to know what was really going on within the program.

Themes that came to light from what the different groups shared

#8:

The Importance of Backwards Planning

Next, we went back to the organization’s strategic plan that they were working on for renewing accreditation. For their curriculum portion, we looked at what the goals were and identified key indicators that programs should include. This helped identify and give shape to the ‘why’ or purpose for this program and the courses offered. It also helped determine the specific goals and outcomes that the program should deliver.

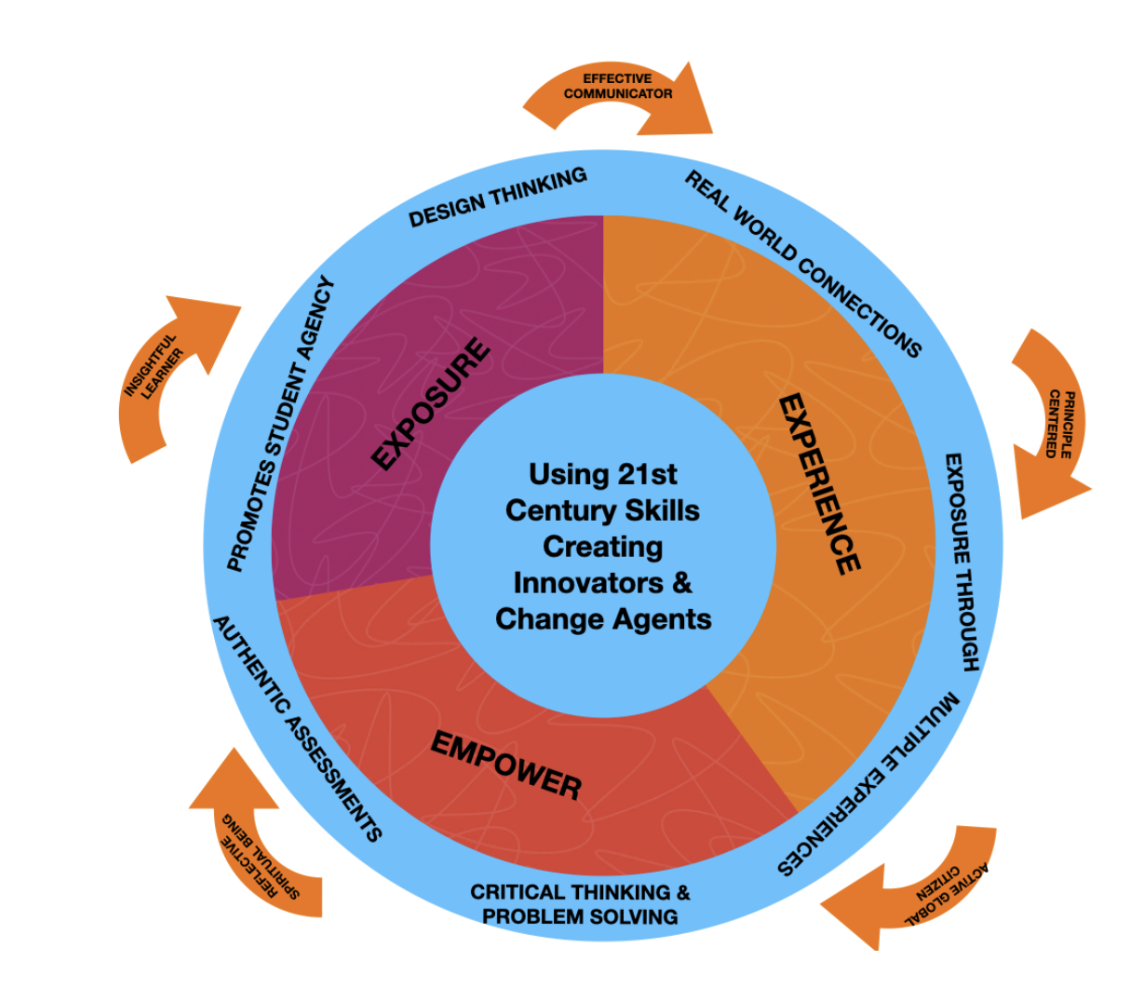

After reviewing several learning frameworks, we created a hybrid that included the key points that administration and teachers were seeking. We looked at how these frameworks could compliment one another and what was currently already being implemented.

As a result, we adapted and modified a visual that the upper school was using. By adapting and modifying it, we were able to create continuity between divisions and honor work that had come before. This new visual was then used as part of the incoming teacher training orientation. As part of our training, we worked through each layer of this wheel and how they compliment one another while also meeting the specific Student Learner Outcomes that were identified.

The new visual created to show the layers and and compliments for the new program overlaid onto what was already in place

Recognizing that many teachers already had full workloads and could be resistant to what could be perceived as a ‘new initiative’, we didn’t want them to look at this as an additional add-on. Instead, we wanted teachers to understand that these courses were a compliment and deeper extension to the work they were already doing with their class. Therefore, we created this image to help visualize the connection to the great work that was already being done by the faculty.

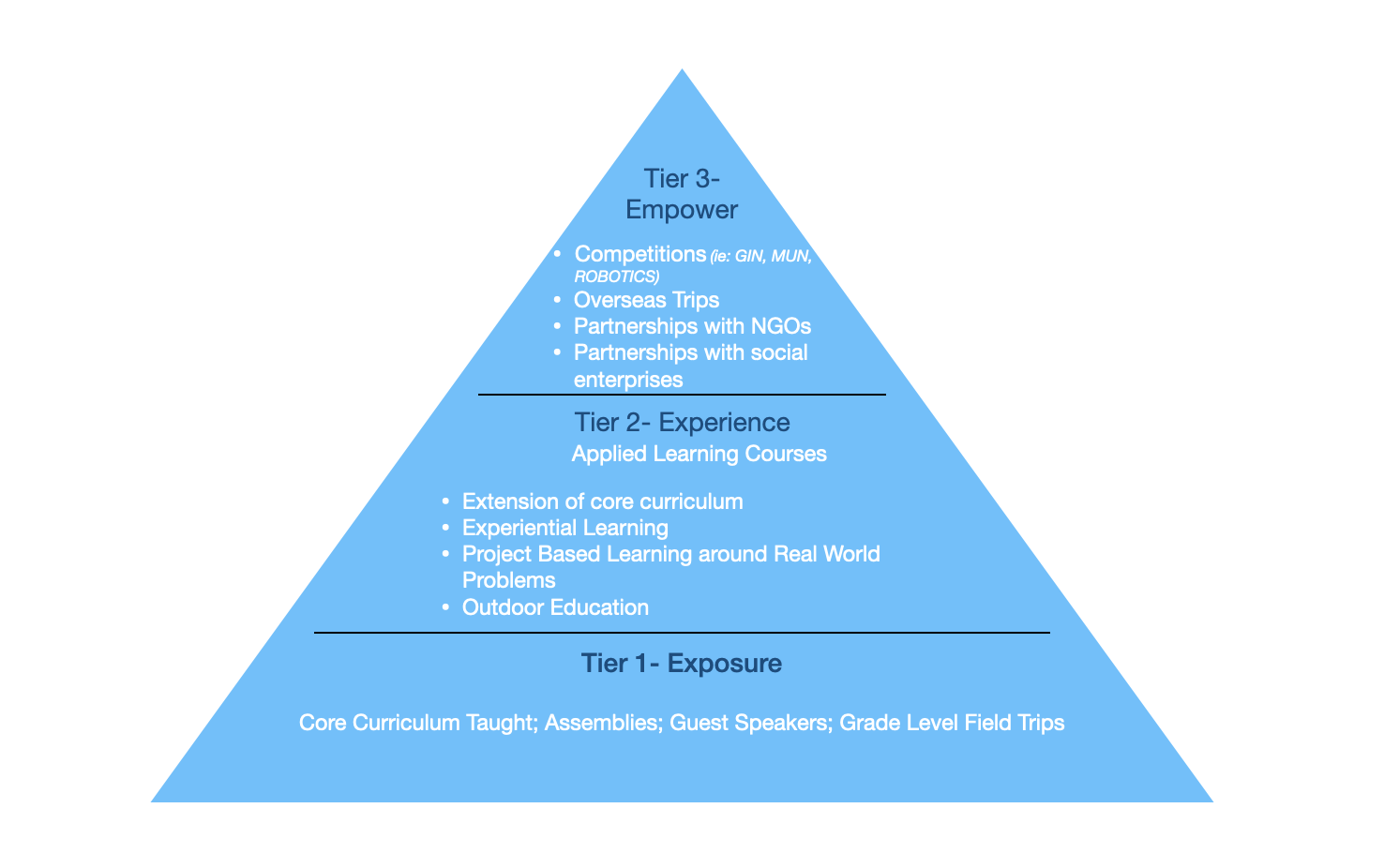

Teachers were already doing Tier 1 and some teachers were working in tier 3. The new courses were the connection between Tier 1 and 3.

The final component was to an audit on the courses being offered- did they match up with the specific criteria that had been identified? From the criteria that we identified, a basic checklist that the faculty and coordinators could use as a lens to review courses that were currently being offered was created. For those courses that lacked meeting the full criteria, if faculty still desired to offer a specific course, coaching was provided and resources were collected to help guide course revision. New courses were added, some were taken away.

What was the outcome?

During the next cycle of implementation, both faculty and students shared that the program had more depth than before. For teachers, there was greater clarity in the purpose for the courses offered. It felt less like busy work and allowed them to teach many of the ‘extra’ skills that they felt they didn’t have time to teach in class; for students they felt like there was more intentionality behind the courses they were taking which created further engagement.

The most effective programs are those that start with the finished results in mind.

Final Thoughts…

While it might seem counter-intuitive, by reversing the planning process, not only are desired outcomes clearly defined, but a roadmap that aligns resources, timelines, activities, etc can be strategically crafted. Not only does this enhance clarity and focus for the program, but it allows potential challenges and opportunities along the way to be identified. Ultimately, backwards planning ensures that each step taken is purposeful and contributes meaningfully to the overall success of the program.

If you or your organization is looking to develop a new program/ curriculum or revise and strengthen an existing program/ curriculum, we’d love to connect and explore how we can assist you.