#11: The Questions We Ask, Determine Our Outcome

“What we design is much richer when we start with the end in mind; for that to be strongly articulated, the type of questions we ask are critical.”

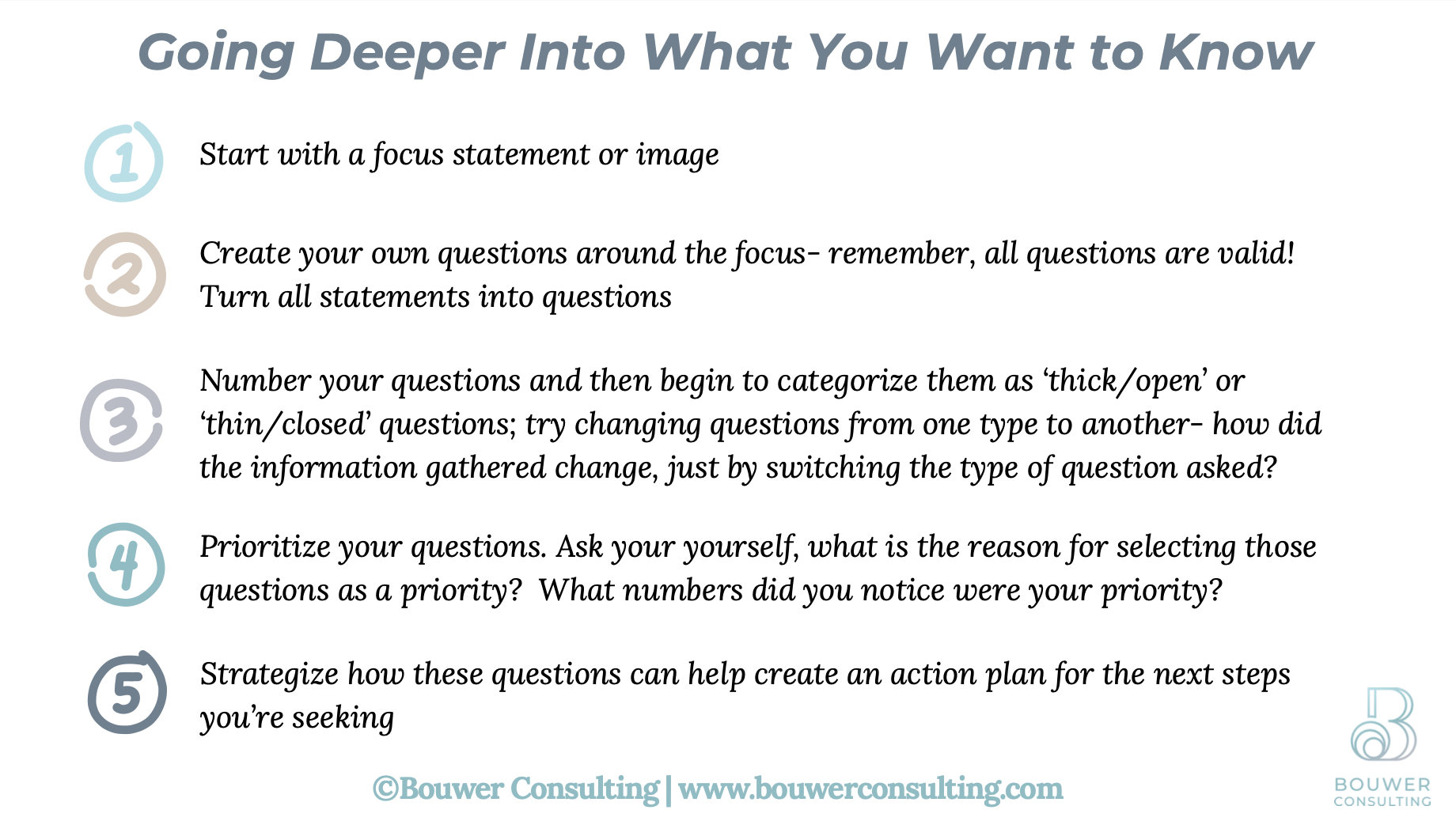

Click below for our free PDF “Going Deeper With Our Questions” cheat sheet

This week is part 3 of our 4 part series where we are exploring the following ideas:

Identifying the type of questions we ask during Program Development

Showing how Backwards Planning can be used in intentional Instructional Design

Providing a specific example demonstrating how Backwards Planning and Intentional Questioning impacts success

Discussing how these skills impact organizational growth and leadership

In the prior 2 blog posts I shared how the types of questions we ask can impact the initial conversations around program planning & development and how Backwards Planning can guide Instructional Design.

In this post, we will explore the intentionality behind our decision-making processes, examining how beginning with the "WHY" not only informs our choices but, when paired with deliberate and thoughtful questioning from the start, leads to successful outcomes. For continuity, I’m going to use the specific program module that was used as the example for blog post #10: Designing With Intent.

Since this is a process post, each step has been broken down and the intentional thought (the WHY) behind each action is provided.

Setting the Stage: Backwards Planning Stage 1 & 3- Identifying Goals & Accessing Prior Knowledge/ Skills Part 1

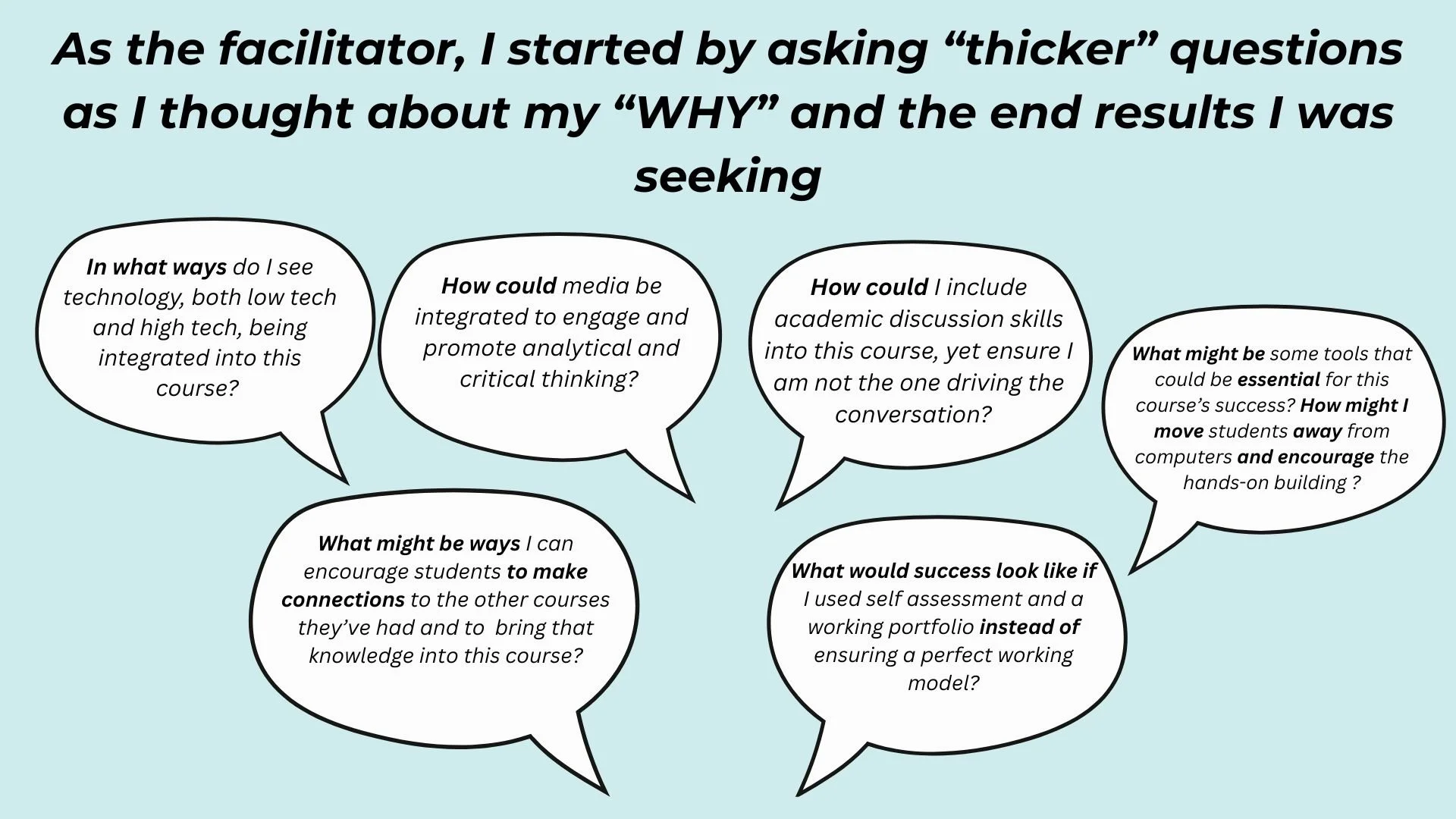

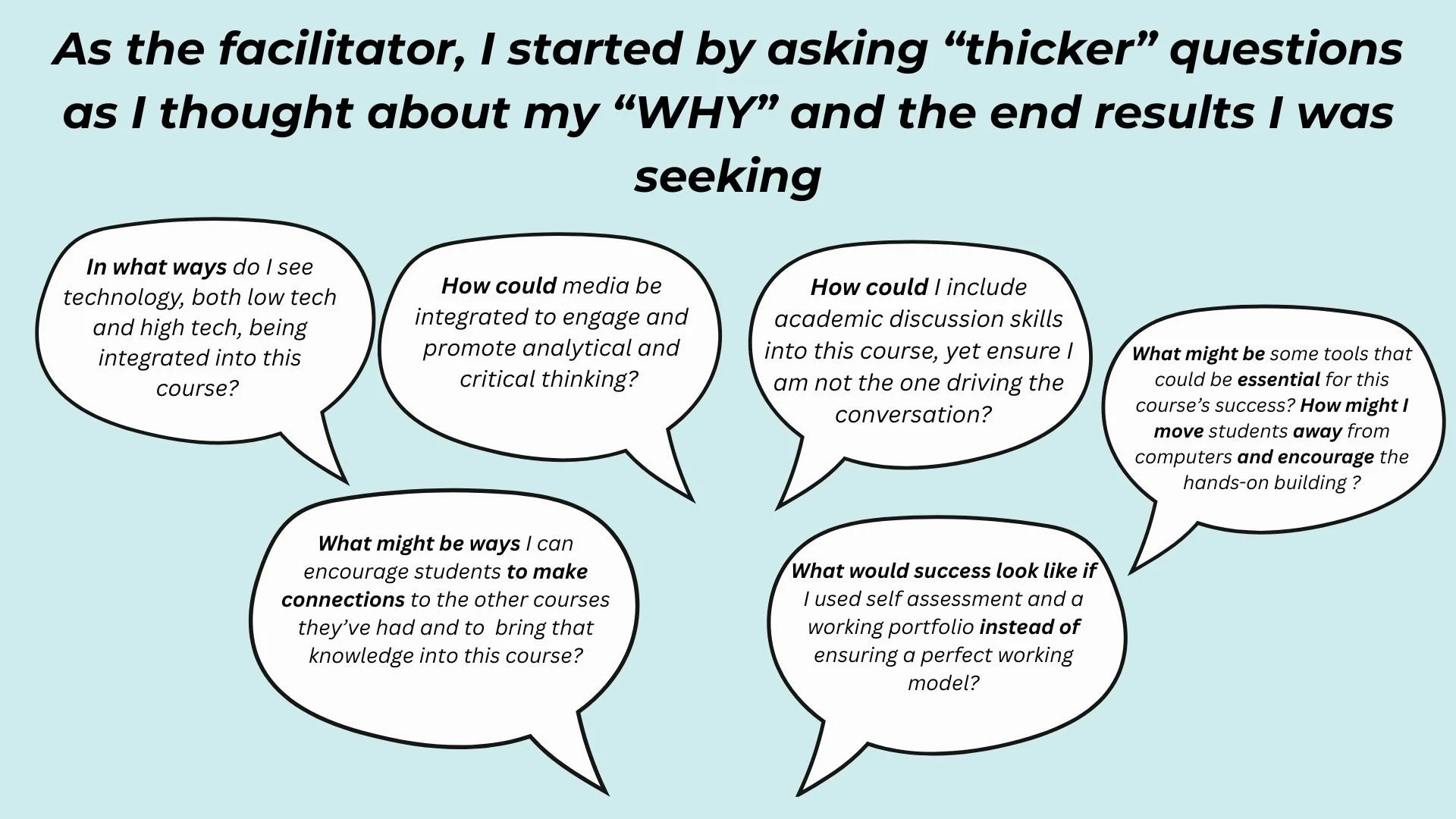

To begin, as I thought about what I desired for students and their experiences in this course, many questions came to mind.

These questions would end up being the guide for a lot of my decision making throughout this course

Coming into this course, participants already had an awareness regarding climate change and the broader impacts it has. They could cite examples, talk about from a ‘head knowledge’ perspective, but since one of the goals for this course was deepening connections and creating a bridge between knowledge and application, a simple role play was used to open the course with.

Each participant randomly selected an identity card with a short story bio on it. They then had to fill out their bio card gleaning information from what they had read (name, location, age, education level, type of wealth, threats to their area, etc). This card would be their new ‘identity’ over the next several activities.

To start, we did a simple activity I called “Who’s most at risk?” that I modified from a resource I had found on the website Practical Action. The WHY/ PURPOSE behind using this as an introduction was for the students to get up, actively move around and get to know each other, and use it as a way to generate a conversation from the start that I was not leading.

I read out various statements and if it related to their persona, they had to either move forwards or backwards a specific number of spaces I had laid out. If they landed on a “chance” number, then they had to flip the card over and do whatever the card said. Their goal was to make it to the ‘safety’ area I had marked.

After reading all the statements (ie: “take 2 steps forward if you’re male”; “take 1 step back if you or child has a disability”; “take 2 steps forward if you own land or a home”; “take 1 step forward if you own a cell phone”....).

There was a lot of chatter, jokes made, and it broke the ice for those who hadn’t had prior classes with one another.

At the end though, I asked 2 questions:

What might these statements have in common and what makes you think that?

What might the relationship between these statements and the course topic be?

A lot of really good discussion was generated and immediately students started making connections to prior courses they had and examples they had observed from their own experiences.

Through the conversation, many of them explained why these statements were or were not beneficial for them to get to the safety area I had marked on the floor. At the end of the discussion, I then asked if they could summarize these statements and the discussion they had in 2 words or phrases, what it would be: the most common words selected were ‘vulnerability’ and ‘structural injustice’.

#11:

The Questions We Ask, Determine Our Outcome

Setting the Stage: Backwards Planning Stage 1 & 3- Part 2

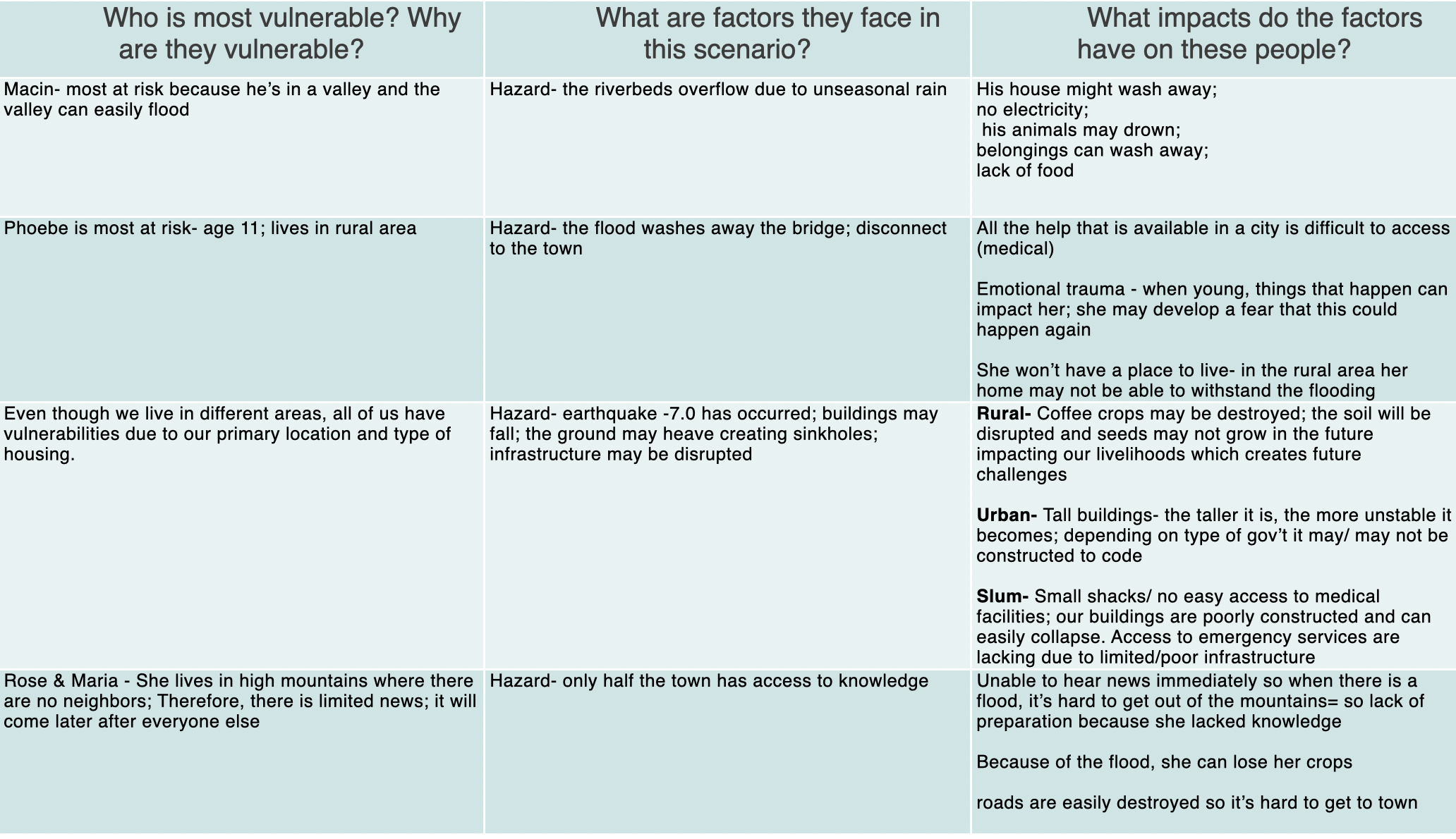

Now that I had the conversation going, I split everyone into random groups of 3 and I asked them to create a 3 column chart on chart paper. The goal for this exercise was to review the analysis process that I had taught in a prior class that they had all taken. In that course, we had talked extensively about factors and impacts and how these play a significant role in the decisions people make as they try to meet their basic needs. My hope was that some of those concepts and skills covered would be brought forward through this exercise.

In this exercise I displayed very brief scenarios and the groups then had to discuss, based on their character profiles:

Who was the most vulnerable in the group?

Why were they the most vulnerable individual in the group?

In the scenario provided, what might the factors be that led to their vulnerability?

What might be an impact on this individual as a result of these factors?

After sharing each scenario, groups had time to discuss and fill out their chart. As a larger whole group, results were shared after each scenario. Some groups found that throughout the different scenarios, the same one or two individuals continued to be the most vulnerable. Other groups found that vulnerability depended on the scenario; while they might be seen as vulnerable in one scenario, they were the least vulnerable in the next scenario.

Sample scenario chart response

Based on the discussions, we then moved observations closer to home. I had found various new clips from the last 6 months from regions representing where everyone was from (floods in Beijing, Malaysia, India, Eastern Europe, the US, etc). As the groups watched these media clips, they wrote down their observations and then classified them as Factors or Impacts; based on all that had been generated so far, groups were then asked to draw initial conclusions.

Building Understanding Based on the Types of Questions Asked

If you recall from my prior post, one of the goals for this course was to create a bridge so that students understood broader global connections (WHAT), but also moved towards the application process for how they might approach solutions to some of the challenges communities face. (HOW/ WHY).

To do this, I wanted students to participate in what I call ‘Quick cycle Research’; however, this is only effective based on the type of questions you ask.

To begin I had each group do a quick image search related to recent floods around the world. Each group member was to contribute 2 photos, so each group would have double the number of photos per group member so there were plenty of visuals.

Why did I have them find images of research floods?

Images in our media are designed to catch our attention and stimulate our interest. If we spend enough time looking at them, our curiosity is peaked and we begin to ask questions about what we see/ what we don’t see/ and about details that we might initially gloss over if we were reading text. Having groups self-select allowed them to have a starting point where they were interested in entering this topic.

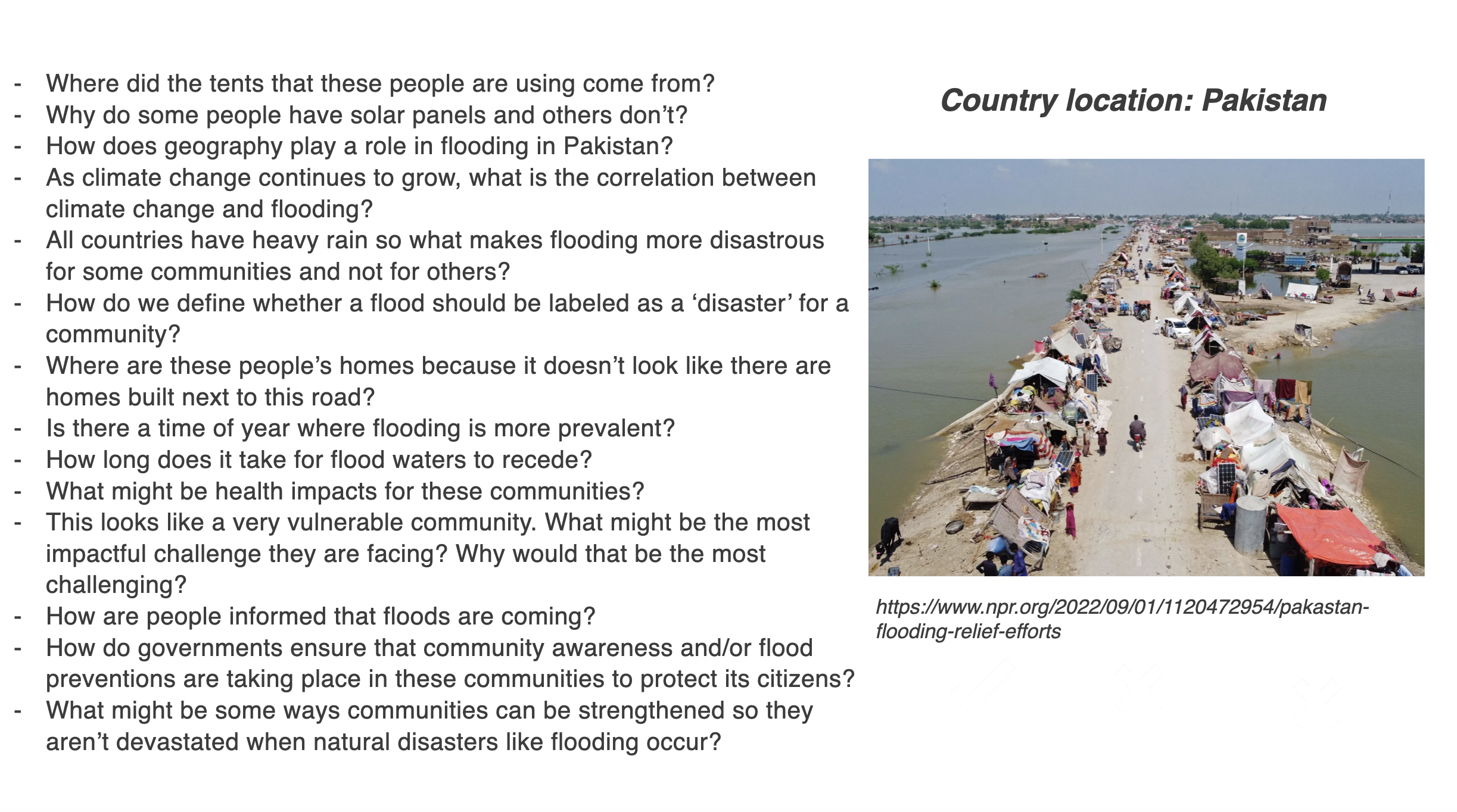

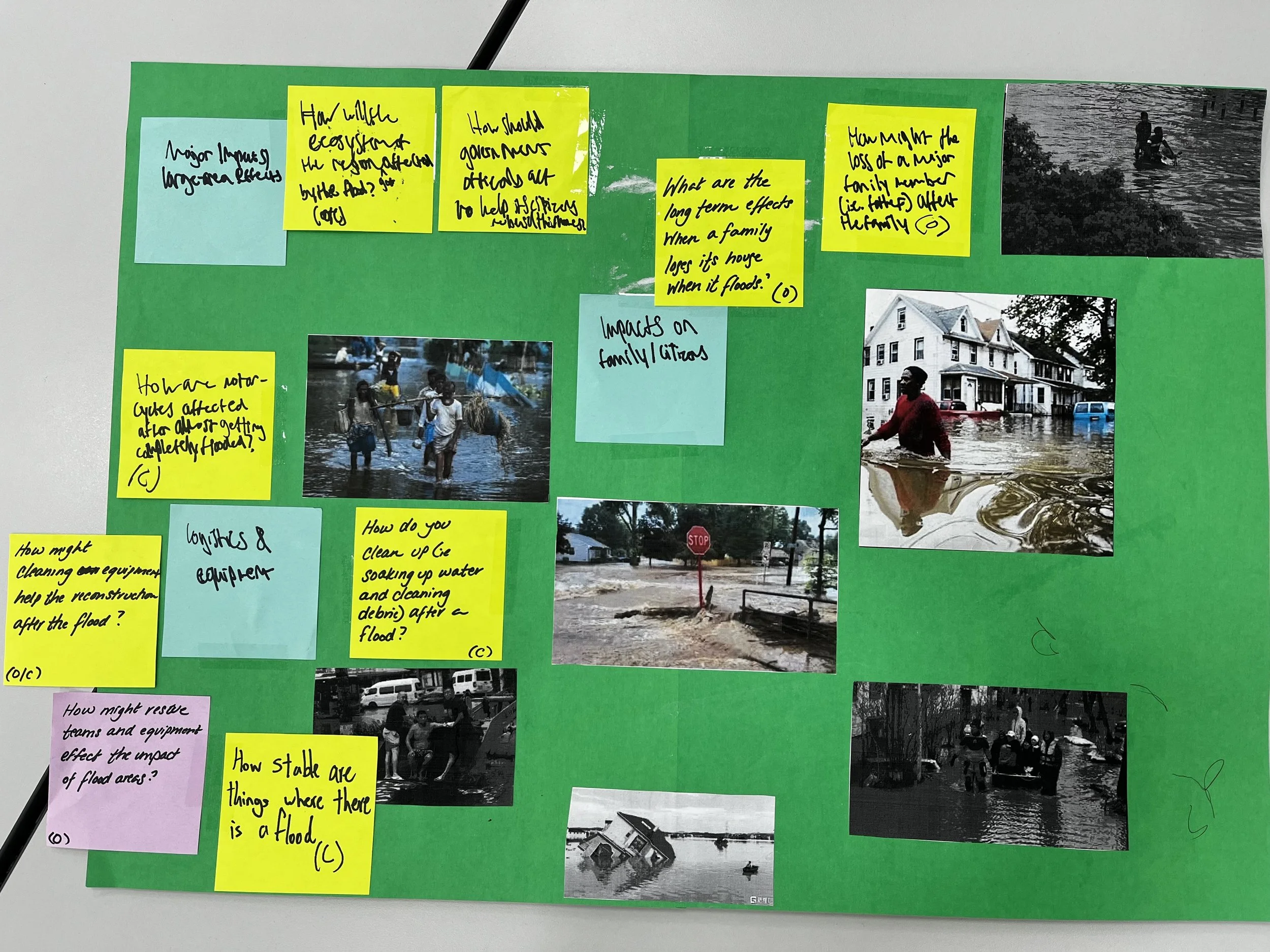

After printing the images, groups then took a packet of sticky notes and began to ask questions about the photos. Any question that came to mind as they carefully observed the photos, they wrote down. At this stage they weren’t to evaluate the questions, judge if they were good or bad, or discuss them; the purpose was to generate as many questions as they could. Since I use the Socratic method a lot in my courses, students were accustomed to the back & forth nature of questions flowing throughout my classes so there was no surprise when I asked them to develop questions.

Also, as I had previously taught the strategy, Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), students were accustomed to evaluating photos and images for information and using that as a springboard for their questions; this was an additional tool they had in their toolbox to help generate questions.

Sample questions using images

Once they had written down all their questions (at least 10), they then began the process of identifying which questions were ‘thin’/ ‘closed’ or ‘thick’/ ‘open’ and labeled them with an “O” or a “C”.

Why did I have them label the questions? Too many closed/ thin questions and they would find themselves boxed in for their research; too many open questions, they may find themselves with too many broad ideas.

The next step was to have them begin to evaluate the type of questions that they asked and begin to sort them. I had them use the following criteria for sorting:

What do your questions have in common?

What patterns are you noticing with the questions you have created?

What might be a category heading for those questions?

Why did I ask them to evaluate and sort their questions?

I wanted them to dig deeper into identifying what they were actually trying to ask. By finding the patterns and commonalities questions had, they began to rephrase questions taking elements of several questions to create better, thought provoking questions.

Sample of a group sort

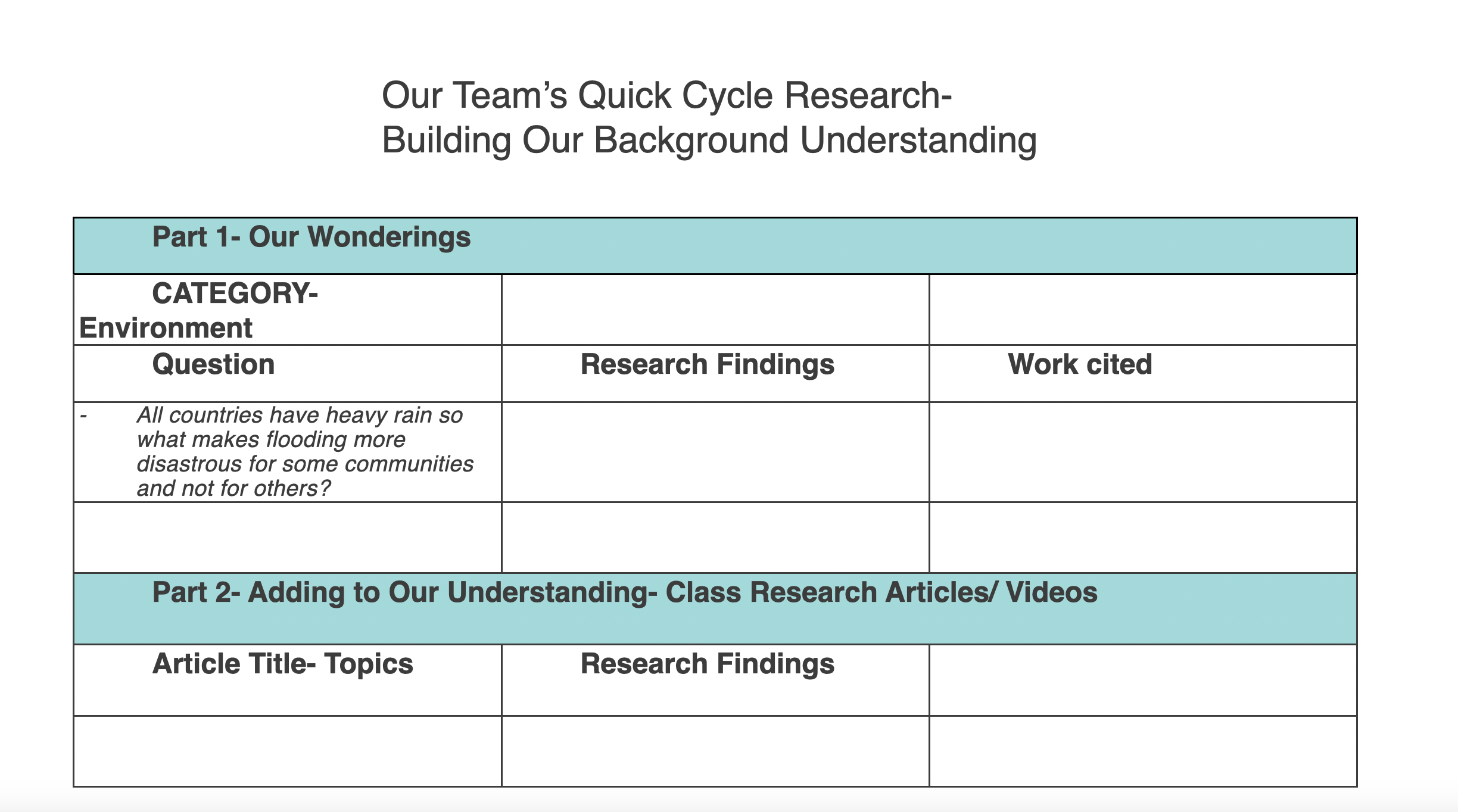

Once questions were sorted and categorized, groups then selected their top 5-6 questions and starred them. These would be the questions that help guide their research process. Having 5-6 group identified questions gave them a platform to explore deeper into, and having them work on a shared document ensured that everyone was aware of the questions and findings.

Sample shared research template

After they felt they had enough information to be able to answer their research questions, I then provided 6 additional articles for them to Jigsaw (each person selecting 1 article to read and share) and added that to their research.

Sample research template #2

Why have them select their own questions and share their research on a shared document?

Selecting their own questions allowed them to identify where they felt was most important to build background knowledge. Returning to the WHY of Backwards Planning, one of the goals for this course was building the bridge between the WHAT and the HOW/ WHY. To ensure success for the overarching goal, students were preparing by not only building knowledge (facts/ details) but also understanding (how to apply the knowledge) about the issue. Each group was able to determine how to enter into the topic based on what they felt they needed more time diving into.

As this was “Quick Cycle Research”, I didn’t want them spending large amounts of time in this process. Having them work on a shared document ensured that everyone was aware of the questions and findings. It also allowed me to assess progress and check for their understanding.

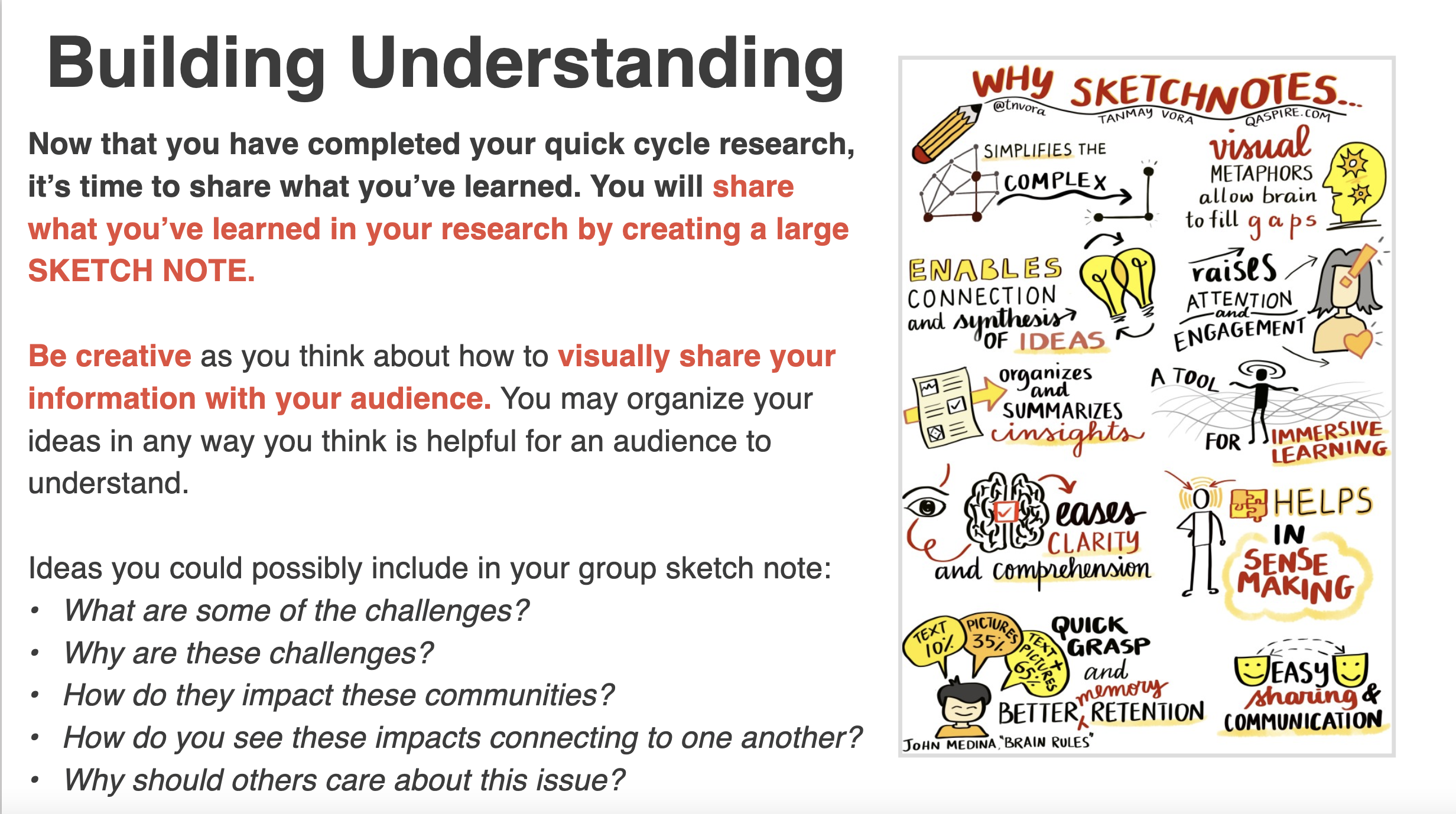

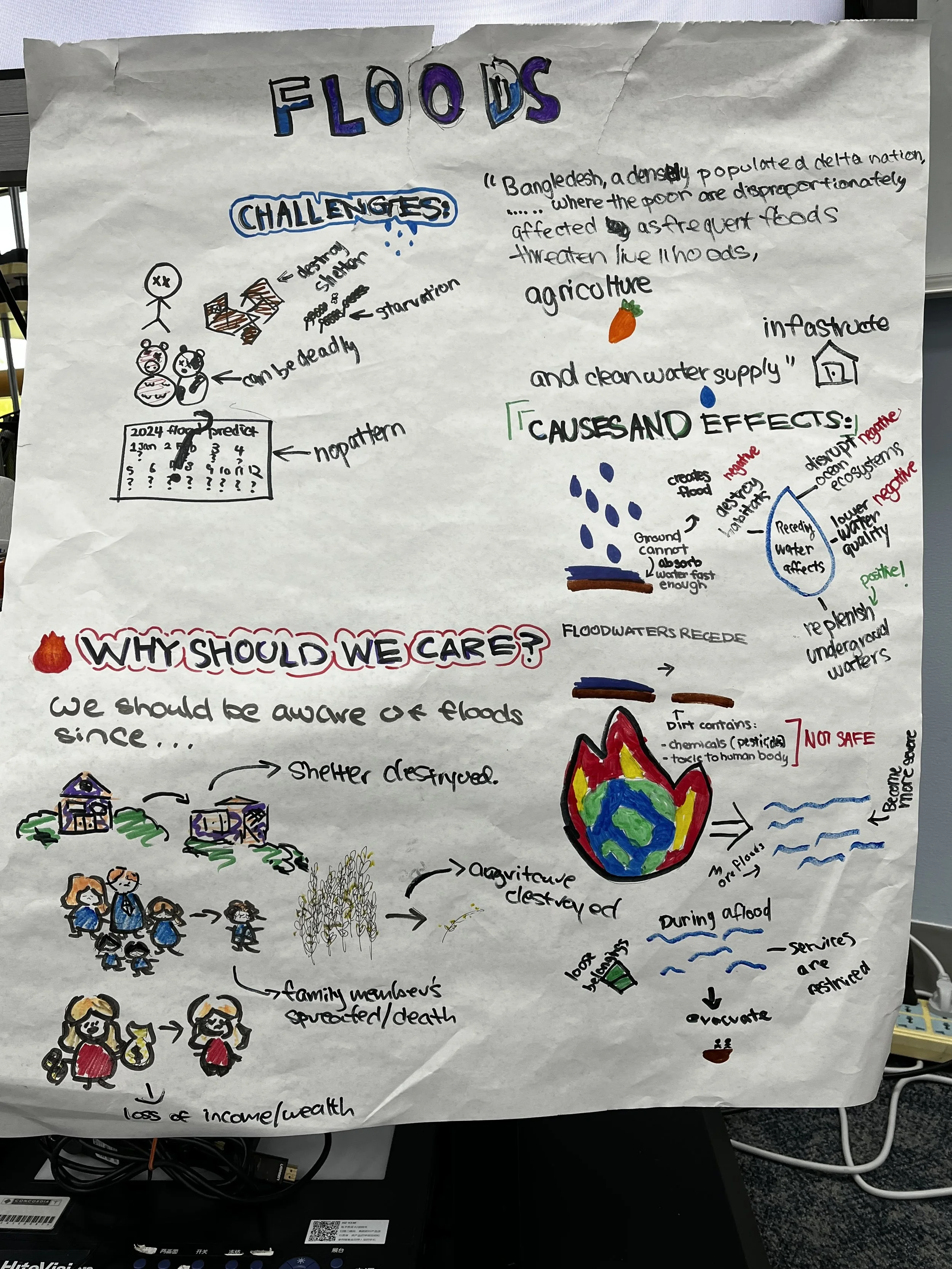

After finalizing their quick cycle research, it was time to share their findings. Groups were asked to take their findings and create a Sketchnote to help them prepare for their presentation.

General guidelines were provided

Why create and share individual group research?

As individual groups presented their findings to the larger group, I scribed key ideas that they shared. By the end, a large summary of everyone’s findings was created.

By sharing the type of questions that had propelled groups into their research, the research findings created new ideas. Often groups spontaneously adjusted their presentation ideas based on what others had shared as they made connections.

Additionally, as they identified potential challenges they might face in the design challenge, possible solutions were shared.

These themes and ideas were then able to be brought into the next stage as they began to test design materials and eventually move into their final design challenge, to create a home that was flood resistant, while ensuring that their specific community needs were met.

Example summary of whole group findings

Conclusion

As previously shared, the outcomes that we seek, whether it’s building a new program, working in instructional design, or facilitating a workshop or lesson, is much richer when we start with the end in mind.

However, for the end goal to be strongly articulated, the type of questions that we ask are critical.

By taking time to pause and reflect on the type of questions that are being posed, we are able to not only challenge assumptions, but we are able to be better informed about the specific challenge we are seeking to solve. This in turn allows us to be better decision makers as we are able to consider multiple perspectives.

Returning to the questions that I had initially posed at the start of designing this course- the outcomes I sought for this course were dependent on the type of questions that I asked myself at the beginning. By starting with my “WHY” and thinking about the end goal I had in mind, it was easier to consider the pathway needed for the course success I desired.

For the students, by the time they made it to their final design challenge, they had a very clear idea for not only their goal, but how they wanted to move forward to achieve it. Because they took the time to establish their “Why” and begin to probe deeply at the beginning, each group not only understood the various elements they would need in order to be successful, they had several ideas already permeating that came from listening to one another’s questions and ideas.

Backwards Planning and Intentional Questions are two strategies that compliment one another. When used together, it creates a more powerful experience and guarantees success for all.

If you’re looking for a collaboration partner to intentionally design a new program or course that you’d like to implement, reach out and connect with me~ I’d love to be a part of your process!